India started its vaccine drive in January, amid plummeting cases and a fair bit of optimism.

The country’s very own Serum Institute of India (SII), the world’s largest vaccine maker, was meant to supply most of the jabs as the country headed towards an ambitious target – covering 250 million people by July.

As part of a World Health Organization (WHO)-led scheme, India even exported vaccines to countries that needed them.

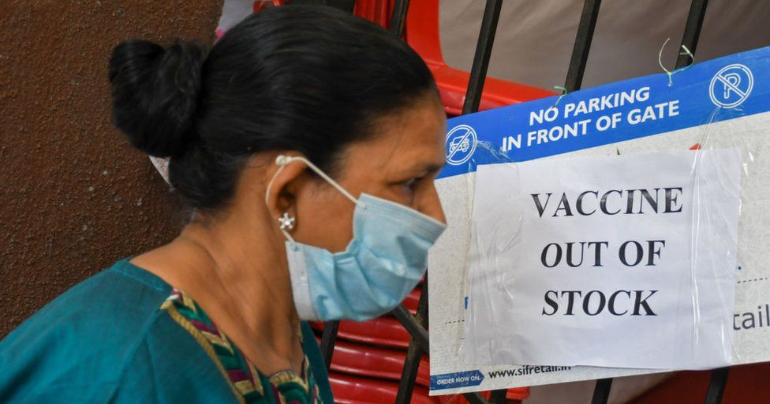

But three months on, Covid cases and deaths are spiking across the country. Only about 26 million people have been fully vaccinated out of a population of 1.4 billion, and about 124 million have received a single dose. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has cancelled exports, reneging on international commitments. Worse, vaccine stocks in the country have nearly dried up, and no-one is sure when more will arrive.

How did India get here?

Demand surged when supply was short

On Wednesday afternoon local time – just as millions of Indians were trying to register online for a Covid jab – the vaccine portal and its accompanying apps crashed.

Starting 1 May, India is opening up vaccination for roughly 600 million more people, to cover 18-44 year olds. But CoWin, as the platform is known, couldn’t handle it.

“I am stuck in an OTP loop of horrors,” said one 33-year-old while trying to register for her jab. OTPs, or one-time passwords sent to mobile numbers, are a favoured Indian way of verifying identity online. She had a string of messages with OTPs, but nowhere to put them.

Others didn’t even get that far – #WaitingForOTP was soon trending on Twitter, and the memes and jokes followed. Eventually the site was back up – but, to the disappointment of more than 13 million people who did finally register, not a single vaccine centre had slots for booking.

These are just a fraction of the 600 million people newly eligible for a jab. There’s also another 200 million or so, 45 and above, who are yet to get their second jab.

Experts say the government should have finished vaccinating people above 45 before opening it up further, especially when supply was low. In fact, this appeared to be the plan until as recently as 6 April, when the health ministry said the drive could not simply be “accelerated” and that it was not yet considering expanding it to all adults.

It’s likely the rapid, unrelenting surge in cases and reports that younger people were increasingly being admitted to hospital with severe symptoms led to the decision.

“They should have held their nerve and focused on the vulnerable,” says economist Partha Mukhopadhyay. “Now they [the 45 and above] have to compete with 600 million new demanders.”

Since the announcement, those who have received no doses or a single dose so far have been queuing up at centres before supply runs out, raising the risk of infection.

But that’s not the only factor that has thrown India’s vaccine drive into chaos.

‘It’s a seller’s market’

Until now, India’s federal government had been the sole purchaser of the two approved vaccines – Covishield, developed by AstraZeneca with Oxford University and manufactured by SII; and Covaxin, made by a local firm Bharat Biotech.

But it’s now thrown open the market to not just 28 state governments, but also private hospitals, all of whom can directly negotiate and buy from the two vaccine makers. And they have to pay far more.

The federal government still gets 50% of stocks for 150 rupees ($2; £1.40) per dose, but states have to pay double that, and private hospitals eight times as much – all while competing for the remaining half.

The sudden transfer of responsibility – it was announced just 10 days ago – left officials with little time to negotiate prices or stockpile vaccines. Especially since vaccine makers still have orders pending from the federal government.

“We are the only country in the world that is allowing sub-national governments to directly buy from vaccine makers. This is not at all well though-out,” says Mr Mukhopadhyay.

The different prices are concerning, says Srinath Reddy, a public health expert who advises federal and state governments on tackling Covid-19.

“All vaccination should be free, it’s for public good,” he says. “And why should states pay a higher price? They are also using tax payer money.”

He fears that it’s now a “seller’s market”, where the poorest Indians are likely to be last in line.

Two private hospital chains have already announced that they will roll-out the vaccine for 18-44 years olds from tomorrow, but it’s unclear how they managed to secure supply when states are struggling. Some have even said they are putting the expansion on hold until more vaccines arrive.

When will the vaccines arrive?

No-one really seems to know. Even if some stocks do trickle in, the crunch will likely continue because the maths simply does not add up.

The federal government still needs another 615 million doses to finish vaccinating everyone above the age of 45 – about 440 million people. State governments are expected to pick up the tab for 18-44 year olds – there are 622 million of them and they would need more than 1.2 billion doses. Even vaccinating 70% – to achieve herd immunity – would require some 870 million doses. This does not account for wastage, which means more stocks are needed.

To be able to administer all of these doses in the next year, India needs to be giving 3.5 million doses a day – it’s behind by more than a million doses right now.

And supply is nowhere close to what is needed. SII is expected to produce about 70 million doses in May, and Bharat Biotech an additional 20 million. That’s a total of 90 million doses a month. They are expected to ramp up further but that will take time.

Other vaccines are now in the mix, including Russian-made Sputnik V, which is yet to be approved in Europe. The makers have already signed manufacturing deals with a host of Indian companies but the infrastructure and approvals for making a vaccine take time. So for now, India is importing the vaccine from Russia and it’s expected to be rolled out in June.

All of this means there will be a supply crunch at least for the next few months. Of course, there was a lot the federal government or even states could have done to ramp up vaccine manufacturing ahead of time.

“If plan A doesn’t work, you should be ready with plan B,” says Mahesh Zagade, former health secretary of Maharashtra, one of India’s worst-hit states.

Why was there no Plan B?

It’s a question many have asked – and the answer seems to be that no-one was preparing for a second wave.

“Our numbers were low and there was this constant narrative that India had beaten Covid,” says virologist Shahid Jameel. If vaccination had kept pace through February and March, he adds, the second wave would have been far less intense.

Experts also recommend a localised drive – that is, targeting the most vulnerable – the elderly or those with co-morbidities – in places where infections are growing fast.

But to do that requires deep district and village-level surveillance and response, which virologists have said has been lacking since the start of the pandemic.

Mr Zagade says breaking up populations into administrative units as small as 25,000 makes it easier to enforce social distancing and enrol people for vaccination by going door-to-door if needed. Instead, the government relied on people registering online or walking in to get their jabs.

So the vaccine drive began to lag even as cases rose, driven up by lax safety protocols and massive public events, from elections to festivals.

And there was no plan B because plan A was based on an assumption that has been proved wrong – that there would be no second wave at all.

SOURCE: BBC

Leave a Comment