African countries are not among those calling out China for its treatment of the mostly Muslim Uyghur population in the north-western region of Xinjiang.

In fact some African diplomats recently attended an event in Beijing and lauded China’s policy in the region.

At least a million Uyghurs are believed to have been detained in Xinjiang in a sprawling network of camps. China faces accusations of forced labour, forced sterilisation, torture and genocide – allegations it denies.

The Chinese government has defended the detention camps, claiming they are vocational “re-education centres” for combating terrorism and religious extremism.

“Some Western forces hyping up the so-called Xinjiang-related issues are actually launching unprovoked attacks on China to serve their own ulterior motives,” Adama Compaoré, Burkina Faso’s ambassador, was quoted as saying at the event in March dubbed Xinjiang in the Eyes of African Ambassadors to China.

The event was also attended by Sudan and Congo-Brazzaville, whose envoy Daniel Owassa reportedly said he supported what China has called a series of anti-terrorism measures in the region, saying he appreciated “Xinjiang’s great development achievements in various fields in recent years”.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) said the gathering was an example of Africa’s silence on a key global concern.

“[It] might be routine diplomacy, but African governments’ willingness to remain silent on Beijing’s suppression of rights has real-world consequences,” Carine Kaneza Nantulya, Africa advocacy director at HRW, said in a statement.

“[Africans] have often justifiably decried other countries’ indifference to their plight and sought global solidarity with human suffering,” she added.

Generational change?

But Ejeviome Otobo, a non-resident fellow at the Global Governance Institute in Brussels, says African leaders and China have a common understanding, based on three main areas: Human rights, economic interests and non-interference in internal affairs.

Increasingly Africa’s largely pro-China position is pitting the continent against the West when it comes to human rights.

During a vote in June 2020 at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva about the controversial Hong Kong national security law, which imposed harsh penalties on political dissent and which effectively ended the territory’s autonomy, 25 African countries – the largest grouping from any continent – backed China.

Months later in October no African country signed up to a stinging rebuke of China’s human rights violations in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Tibet, which was backed by Western nations.

HRW accuses Africa’s leaders of prioritising economic benefits from China at the expense of other global concerns.

Yet Eric Olander, co-founder of the China Africa Project, says for African policymakers not antagonising Beijing “is a much more important foreign policy priority”.

“What these critics don’t seem to understand is that as poor, developing countries – many that are also highly indebted to Beijing and depend on China for the bulk of their trade – they are not in a position to withstand the immediate blowback that would result from upsetting China,” he told the BBC.

Another big factor is a decades-old relationship which was cemented in 1970 when African countries played a critical role in helping China re-join the United Nations amid protests from the US.

“Since then the relationship has only strengthened,” Cliff Mboya, a Kenya-based China-Africa analyst, told the BBC.

“For 30 years now China has made it a tradition that its foreign minister visits Africa first every new year – this is not just symbolic but signals that they are invested in a long-term relationship and this makes a big impression on Africans.”

Younger Africans may not be so impressed – they have an overwhelmingly positive view of the US and its development model, according to a recent Afrobarometer study.

But the older generation and government leaders feel differently – and their decision to turn to China for infrastructure funding especially in the last 20 years – has transformed the continent’s landscape with expansive roads, bridges, railways, ports and an internet infrastructure that has ensured the continent is not a pariah in the digital economy.

Some of these projects are part of China’s multibillion Belt and Road Initiative which 46 African countries have signed, says Mr Otobo.

“Where is the equivalent from the West?” he asks, adding that it would be difficult to match the scale of China’s funding.

The lack of transparency in the deals signed to fund these massive projects has fuelled suspicion of an insidious plot to entrap the continent with loans it cannot pay, says Mr Orlander, although this “debt trap” theory has been debunked.

And debt relief and access to Covid-19 vaccines are likely to be key themes at the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation (FOCAC), the high-profile three-yearly event, which will be held in Senegal later this year.

Vaccine diplomacy

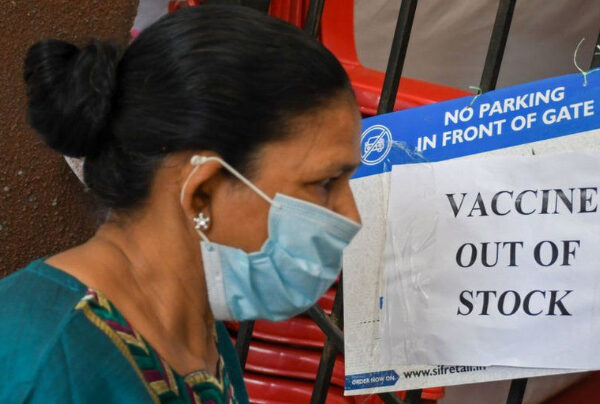

Since the pandemic hit, Chinese flags have been a common sight at airports on the continent signalling the arrival of vital donations such as personal protective equipment and lately of Chinese-manufactured vaccines.

China’s so-called vaccine diplomacy has so far reached 13 African countries, which have either bought them or have benefited from donations.

In comparison there has not been any direct support from the UK or the US except through the global Covax initiative – which is also supported by China. Covax has administered 18 million doses so far in 41 African countries.

Using access to Covid-19 vaccines as a tool of influence around the world is an ongoing race among global powers.

In March UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab urged developing countries to wait for the “gold standard” vaccines rather than those from China and Russia.

New US Secretary of State Antony Blinken sees the situation as less of a race, recently telling African students: “We’re not asking anyone to choose between the United States or China, but I would encourage you to ask those tough questions, to dig beneath the surface, to demand transparency, and to make informed choices.”

Western powers know that they cannot compete with China in terms of loans and infrastructure – there have been no retaliatory measures for those taking Chinese aid or being overly partisan towards Beijing. Instead they fall back on mantras such as calling for democracy and investment free of corruption.

For this reason, it is inconceivable that in the near future any African country would seek to take a Chinese leader to The Hague over its treatment of the Uyghurs – as happened to Aung San Suu Kyi in 2019 when she was leader of Myanmar and The Gambia’s former justice minister brought a case against her country’s treatment of the Rohingya Muslim minority.

Abubacarr Tamado was backed by the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, a group of 57 mainly Muslim countries, 27 of them African. The move, applauded in the West, has so far resulted in the International Court of Justice ordering Myanmar to take measures to prevent genocide.

Leave a Comment