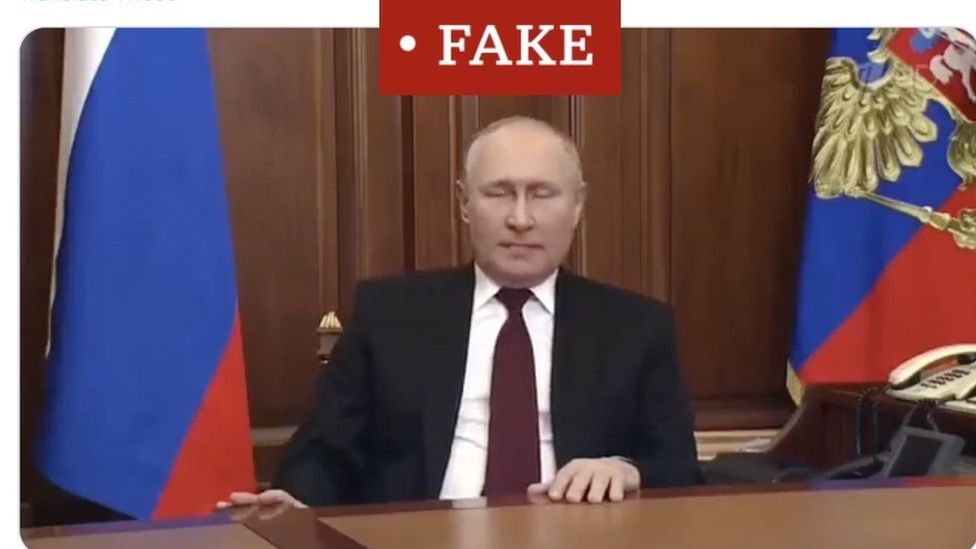

A deepfake video shared on Twitter, appearing to show Russian President Vladimir Putin declaring peace, has resurfaced.

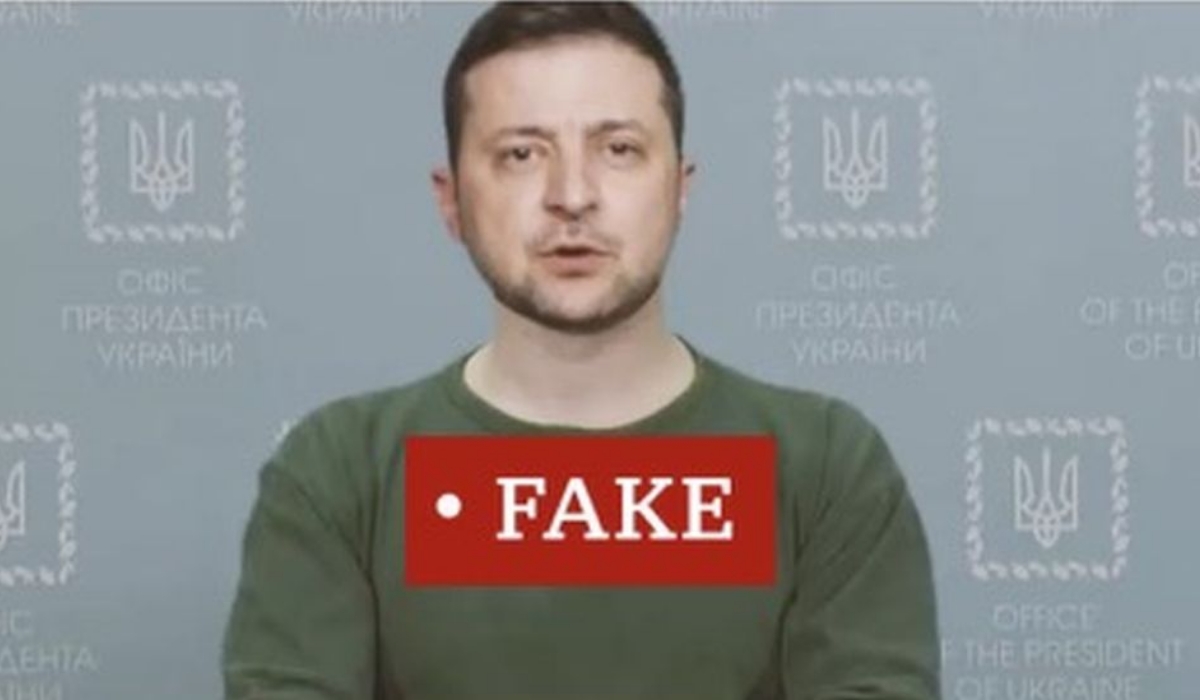

Meanwhile, this week Meta and YouTube have taken down a deepfake video of Ukraine’s president talking of surrendering to Russia.

As both sides use manipulated media, what do these videos reveal about the state of misinformation in the conflict?

And are people really believing them?

The unconvincing fake of President Zelensky was ridiculed by many Ukrainians.

Volodymr Zelensky appears behind a podium, telling Ukrainians to put down their weapons. His head appears too large for and more pixelated than his body – and his voice sounds deeper.

In a video posted to his official Instagram account, the real President Zelensky calls it a “childish provocation”.

But the Ukrainian Center for Strategic Communications had warned the Russian government may well use deepfakes to convince Ukrainians to surrender.

An ‘easy win’ for social media

In a Twitter thread, Meta security-policy head Nathaniel Gleicher said it had “quickly reviewed and removed” the deepfake for violating its policy against misleading manipulated media.

YouTube also said it had been removed for violating misinformation policies.

It had been an easy win for the social-media companies, Nina Schick, author of the book Deepfakes, said, because the video was so crude and easily spotted as fake even by “semi-sophisticated viewers”.

“The platforms can make a big hoo-ha about dealing with this,” she said, “when they aren’t doing more on other forms of disinformation.

“There are so many other forms of disinformation in this war which haven’t been debunked.

“Even though this video was really bad and crude, that won’t be the case in the near future.”

And it would still “erode trust in authentic media”.

“People start to believe that everything can be faked,” Ms Schick said

“It is a new weapon and a potent form of visual disinformation – and anyone can do it.”

The many faces of deepfake technology

A deepfake tool letting users animate old photos of relatives has been widely used and the company behind it, MyHeritage, has now added LiveStory, which allows voices to be added.

But there was a mixed reaction last year, when South Korean TV network MBN announced it was using a deepfake of newsreader Kim Joo-Ha.

Some were impressed how realistic it was, others concerned the real Kim Joo-Ha would lose her job.

Deepfake technology is also being used to create pornography, with a proliferation, in recent years, of websites letting users “nudify” pictures.

And it can be used for satirical purposes – last year, Channel 4 created a deepfake Queen to deliver an alternative Christmas message.

The use of deepfakes in politics remains relatively rare.

But a deepfake former US President Barack Obama has been created, to demonstrate the technology’s power.

When detection goes wrong

“The Zelensky was a best-case deepfake problem,” Witness.org. programme director Sam Gregory said.

“It was not very good, for a start so was easily detected.

“And it was debunked by Ukraine and Zelensky had rebutted it on social media, so it was an easy policy takedown for Facebook.”

But in other parts of the world, journalists and human-rights groups feared they had neither the tools to detect nor the ability to debunk deepfakes.

Detection tools analyse the way a person moves or look for things such as the machine-learning process that created the deepfake.

But last summer, an online detector suggested a genuine video of a senior politician in Myanmar, apparently confessing to corruption – debate remains over whether it was a real statement or a forced confession – was a deepfake.

“The lack of 100% proof either way and people’s desire to believe it was a deepfake reflects the challenges of deepfakes in a real-world environment,” said Mr Gregory.

“President Putin was made into a deepfake a few weeks ago and it was widely regarded as satire – but there is a thin line between satire and disinformation.”

Leave a Comment