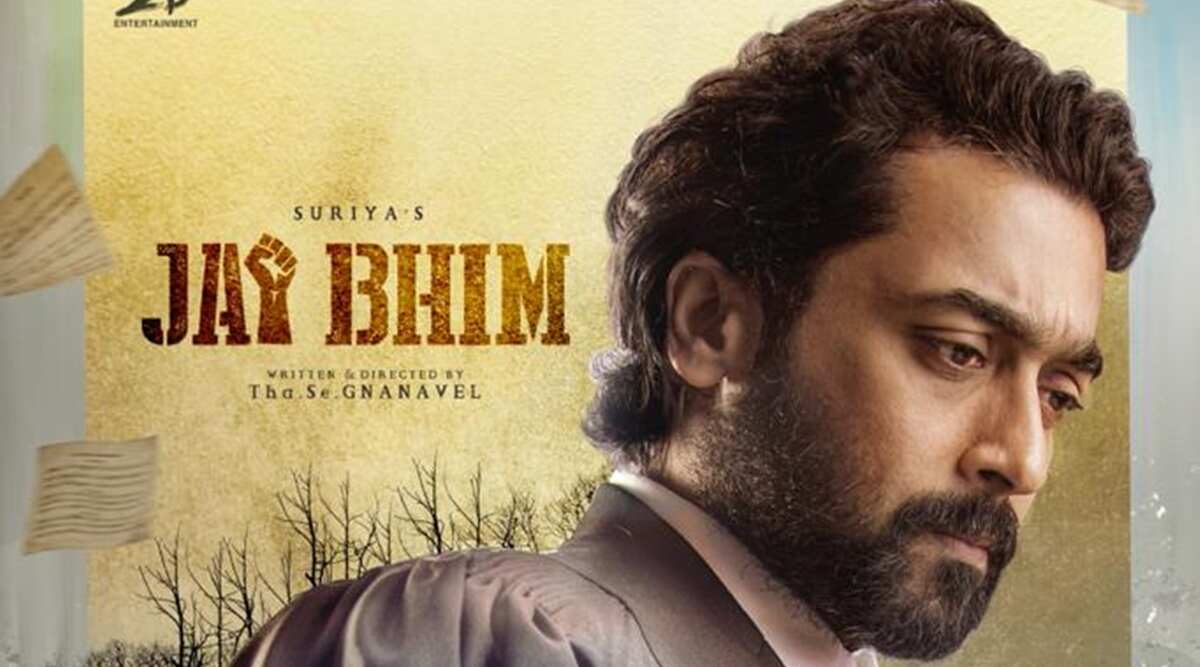

‘Jai Bhim’ is perhaps one of the boldest films to have come out of Tamil cinema. It doesn’t dare turn its back on hitting where it hurts the most, and its politics is not weighed down by the presence of a star like Suriya

At one point in this nearly three-hour-long film, there is a goosebumps-raising moment that has a tribal woman — also the protagonist — turning her back on power, refusing to bow down to the system of dominance that has exploited the fruits of their labour, quite literally. Looking at it purely from the point of view of Tamil cinema’s masala conventions, it is essentially a “mass” scene written for a Dalit character to give her a chance to look at her oppressors in the eye and perhaps tell them: “You cannot break me.”

Senggeni (Lijomol Jose), the wife of Rajakannu (Manikandan, in yet another brilliant performance) who is fighting a lonely battle in the road to justice for husband’s custodial torture and death, gets this rousing moment because of her lawyer Chandru (Suriya). Or rather, because of the backing of a huge Tamil cinema star. Does it reflect reality? No. But does it work as a self-congratulatory, mass scene? Yes. It is also, thanks to Sean Roldan’s pummelling music, a really good stretch that communicates the intention that went into conceiving such a placement in the first place. Yet, something seems broken. Either the desired effect it has on us or the scene construction feels superficial at some level.

Mind you, this superficiality doesn’t stem from Jai Bhim itself, but from the consciousness of having a Tamil cinema star playing a Saviour and leading from the front. Props to Suriya and to an extent Tha Se Gnanavel, the film, thankfully, doesn’t suffer from the onslaught of the Saviour Complex. For, Suriya comes across more of an ally here. But this doesn’t take away the point that the scene discussed above is a testament to the tiny trade-offs you will have to pay, in order to mainstream-ise stories of injustice and exploitation — all of which has now come out of the Dalit movement. Are we ready to forgive and forget this stream of consciousness for these trade-offs, is a good place to leave for introspection. While in the case of Jai Bhim, it is both a yes and no. But these are problems outside of the film.

As for Jai Bhim, it is perhaps one of the boldest films to come out of Tamil cinema. Most of you might confuse its boldness with the film’s ghastly violence, showing the extreme of police brutality and custodial torture (let me spare the details, but some of these scenes are really disturbing). But that is not it. Consider the way it opens and you will understand where I am going with this.

The opening sequence has a police officer segregating suspects based on their caste. He asks, “nee endha aalu (which people are you?).” If they are Dalits or from the tribal community, they are made to stand in a separate group while suspects from dominant and intermediate caste groups are given a free hand. False charges are slapped against Dalits; they are poached and preyed on by officers in-charge, to close the pending cases.

Perhaps what is more important is, there has never been a recent Tamil film where the names of dominant caste groups are explicitly mentioned, in the fear of the ripple effect it might create. There is, in fact, a scene where a dominant caste group member can be heard saying, “Unga kudusai-ya kollutha evalavu neram aagum (how long do you think it’ll take for us to set your house on fire).” But Jai Bhim doesn’t turn its back on all that. The politics here is not watered down; it is direct and takes an incisive look. It doesn’t punch down, but up. This is a film that strips down the individual components of caste, law enforcement and justice system and questions each of them on the witness stand.

What Tha Se Gnanavel also gets it right is the manner in which Dalits and people from tribal communities are exploited for their labour. Rajakannu earns a living by making bricks for his oppressors, but he cannot build a house for himself. He is called on every time there are rodents (or snakes) in the fields but isn’t allowed to touch or strike a conversation with a dominant caste member — he gets shooed away by a lady, when he says they come from the same village. For almost close to 40 minutes, we get to see the myriad ways caste takes shape in Rajakannu’s life and the irony plays out beautifully, even if this may sound slightly insensitive.

Jai Bhim turns into a courtroom drama when Rajakannu, along with three others, is forcefully taken into custody. Despite its run-time, there is not a single scene that looks dull, and there is something constantly happening. Even the courtroom scenes, which may suffer from familiarity in another film, brim with an undying spirit. Suriya plays a social activist-cum-lawyer Chandru, based on the real-life person. There is simmering anger in Suriya’s eyes that is even throughout. But the anger doesn’t reduce Suriya to a rabble rouser; it shows dignity too.

These are all the merits. Now let us address the elephant in the room: Jai Bhim, if anything, is a sad yet necessary addition to the long list of films about oppression that, if you come to think of it, may not transcend beyond the OTT crowd and reach its primary source audience — in this case, the largely ignored Irular community. Are we fake-congratulating ourselves by just giving them mainstream attention? How do we iron out this disparity?

Leave a Comment